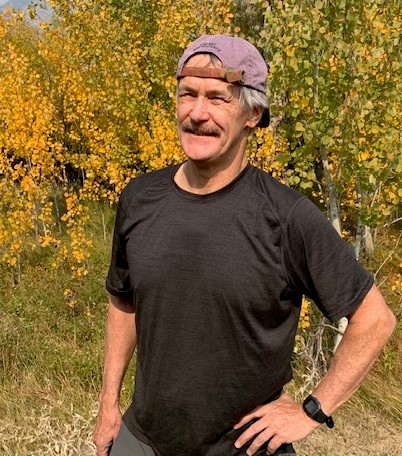

I have utmost respect for public school teachers. I owe my career in writing to their commitments. Today, I substitute-teach and my respect for everyday teachers has never been greater. John Davis, our Issue 3 featured writer, taught English, creative writing, and history for 40 years in public schools.

Besides believing in education, it turns out we have a few other things in common. We’ve run marathons and own records in other footraces. We both tend peach trees. And, as young men, we worked in factories making garage doors. What are the odds of that? Though 2,400 miles separate us, I sense a kindred soul.

Coming from the southern coast of a Great Lake and from the Great Pacific Northwest, we meet on this page. We touch upon teaching writing, his poetry, fresh ginger, military service, and the mystery of melting snow. I hope you enjoy his poems and this interview. — Stephen FitzGerald, Alphabet Box editor.

On writing.

Who or what was your earliest influence that got you started writing?

In high school, we studied poetry in the Sound and Sense anthology. Most of the authors represented had been dead for many years. I got the impression that to be a successful poet, you had to be dead. However, one poet was not dead. William Stafford. I admired his poem “At the Un-National Monument Along the Canadian Border.” A year later, when applying to colleges, I noticed that Stafford was teaching at Lewis & Clark College in Portland, Oregon. That was good enough for me.

I took a couple of classes with Stafford but wrote very little. Richard Hugo visited the college and gave a reading which impressed me. His poems spoke of softball and bourbon. I had never seen those in a poem. There were multiple possibilities in a poem. After I graduated, I worked in a garage-door factory. Bored out of my mind filling 4,000 holes a day with glue, I would write out a poem each night and work on memorizing it the next day.

A year later, I began teaching high school and did a particularly bad job at teaching poetry. I enrolled in an extension class in 1980, with local poet Beth Bentley, and I began to write. When I had to stop marathon running because of knee injuries, poetry became a new obsession. I haven’t stopped.

Has you ever taken a break?

No. I’ve kept at it. It’s medicine. It helps me sort the day-to-day.

How would you compare your poetry today to your earliest?

I was scared shitless to show my first efforts, but eventually gained a bit of confidence. As Stafford famously advised, “Lower your standards.” My writing is more musical now. I pay attention to the rhythm and sonics.

Is there a common theme or basis that you’ve pursued in your writing?

I have written a series of poems concerning my Coast Guard experiences, as well as my garage door and sports efforts. I don’t eliminate love poems, though my last two relationships ended because of love poems I had written. It’s proof of the power of words.

When I sit down to write, which averages four to five days per week, I allow anything to happen.

When you see books or movies prefaced with based on a true story, do you think poetry should be likewise prefaced?

My poems are based on the human experience. Why let facts get in the way of a good story. All my poems are autobiographical. All my poems are fiction.

Do you think poetry matters more or less than it did 10 years ago?

Poetry is trying to express the un-expressible. Art redirects our senses to view the world through a different lens. Poetry enters into that realm. With the Internet, there are thousands of journals sporting poetry. The number has increased exponentially in the last 10 years. There’s more poetry available than ever before.

On your Alphabet Box poems.

Tell us a bit about “Stationed in Yorktown.”

It’s based on my Coast Guard experiences based in Yorktown, Virginia, as well as the site of the Revolutionary War battle. When I was on liberty, I would run over the battlefields.

Poems… they have a way of creeping into past experiences.

What inspired you to write Stationed?

Many years after my Yorktown experience, I thought of that memory and the memory of wanting to be home. I address that in the final four lines.

In July 2021, I wrote several poems about my Coast Guard experiences 40-some years earlier. When I find a vein, I dig into it and grab whatever I can. It may close up and not open again for several years. Stationed was an effort I wrote in one sitting.

Something I noticed was your use of “like mine.” But not the words “our” and “we” — indicating to me the separation of time, of their history from your history. It made so much sense. Then, in the poem’s last line, your choice of “us” blew me away. This doesn’t lead me to a question, but I’d be interested in your comment.

I suppose I was trying to morph the poem into something larger than I.

How many drafts to finish it?

One to two drafts and a bit of tinkering. Change this. Try that. I let poems breathe like a good Bordeaux. After a bit, they mature and go where they want to go.

“Inspection” seems as if it could have come from a personal diary or journal.

Much of that poem is from personal experience. Lamet is a real person.

In the ’70s, a dude was not a dude unless he had hair that at least covered his ears. O those days. I did wear a short hair wig at Coast Guard drills.

Lamet wore one once. It was fake as hell… sloppy, plastic glow, weak neckline. I was about to answer yes when the officer asked us the question. He didn’t know I was wearing a wig. O those hair days of stuffing my locks under a nylon wig cap, securing it with my girlfriend’s bobby pins and shaving the back of my neck. Now, with my receding hairline, I get a good laugh.

“Inspection” took a few drafts and a lot of tinkering. The italicized lines are direct quotes or as near-direct as I can remember. One tends to remember words spoken toward you when your adrenaline is pumping.

For whom do you write poetry?

Most of what I write will never be read by anyone else, except my dog Lilly.

Unless I’m writing a tribute or a love poem, I don’t think for whom I’m writing. I write and if I think the poem has substance that someone might like, then I’ll share it (with them). I don’t want to burden others with poems that are weak. I consider my poems an offering.

I trade poems with a fairly well-known poet. We toss poems back and forth most weeks. During National Poetry Month, we write a poem a day and swap them back and forth. One rule, if there is one: No criticism. Only praise. We can get criticism elsewhere.

I’ve been a member of a poetry group for the past 20 years. We give each other plenty of feedback. It’s not cruel. It’s honest… and isn’t that the greatest compliment you can give to someone?

On teaching.

Where did you teach?

I taught in a semi-rural town in Washington state, beside the Salish Sea.

What did you enjoy about teaching?

The creative writing course I introduced was the best course I taught. I enjoyed teaching teenagers. Some teachers were afraid of teenage energy, but I loved it and the wacky sense of humor. How refreshing.

Sometimes students, new to poetry, would dash off incredible pieces. They didn’t feel any restrictions and so their pencils blasted away and the sparks flew.

I loved their frankness and honesty. We laughed and laughed, and I’d subtlety get them to go farther than they might in taking chances with their assignments.

I hope they gained more confidence in themselves and learned to respect the differences in others.

I taught high school English and creative writing for 40 years, before retiring four years ago. I’m still in touch with several former students.

On the U.S. Coast Guard.

At what age did you enter the military?

Nineteen.

What drew you into the service?

Fear of being sent to the battlefield jungles of Vietnam.

What’s your status now within the Coast Guard? Retired?

Completely withdrawn from it.

Your takeaway from serving? Positive, negative?

I bitched about it a lot when I was in it.

In retrospect, it was good for me to give back to my country. A teacher gives and gives and gives. I suppose my giving as a teacher was an extension of my time in the military.

On Miscellany.

Living on an island, do you have a favorite seafood dish? Or other foods you enjoy?

Shave a bit of fresh ginger. Add it to a cup of maple syrup, which you melt down to a thick “gravy.” Pour it over King salmon and bake. Your tastebuds will love more than they have ever loved.

Ripe peaches are fruit of the gods. I have three peach trees in my yard. To eat a peach: Adore it. Hold it deftly. Bite in. If it’s a chin-dripping peach and the juice dribbles down your chin, you are approaching Nirvana. Tongue the sweet meat around your mouth and swallow.

Do you have a passion unrelated to writing?

I play rock ‘n’ roll and blues in three bands. I ski. I hike. I kayak. I garden. I eat peaches.

How do you view the writing community on Twitter?

I don’t tweet. I don’t drink. I don’t use drugs. I don’t smoke. I don’t drink caffeine. But I can swear. I was a sailor.

What books are you reading for pleasure, or that you’ve finished, that you recommend?

A Good Scent from a Strange Mountain (by Robert Olen Butler). The Splendid and the Vile (Erik Larson). I read Cold Mountain (Charles Frazier) for the fourth time.

Have you ever been to Cleveland, Ohio?

No. Have you been to Seattle?

Yes, while hitchhiking in my 20s. Among ‘non-writers,’ who do you admire most?

Harriet Tubman, Winston Churchill, George Washington, my mother and father, Nelson Mandela and Brian Wilson.

How many collections have you published?

Gigs and The Reservist. Both publishers are out of business.

This would be the toughest Q for me to answer. Your three favorite musical artists or bands?

Just three??????? This is your toughest question.

Bob Dylan, The Beatles, McCoy Tyner, Linda Ronstadt, Miles Davis and Muddy Waters.

Is there a question you were hoping I’d ask?

Yes. Where does the white go when the snow melts?