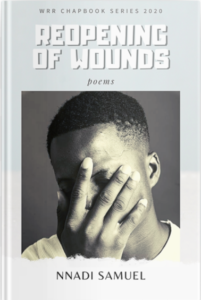

Of the 400+ entries received for this issue of Alphabet Box, one writer stood out. Nnadi Samuel. The voices in his submitted poetry consistently and perfectly balanced the real and the ethereal. AB is pleased to present two of his poems — There is a Gnawing Need for Sugar and Nature knows a little about Slave Trade — both of which he discusses in this interview.

From Cleveland in the United States, I posed questions. From Lagos in Nigeria, our featured writer for Alphabet Box’s fourth issue, answered. We touched upon the craft of writing, a bit of his childhood, writer’s block, the “stereotype of grief,” the meaning of his name, and his next book, Subject Lessons, for which I’m looking forward.

I invite you to get to know Nnadi Samuel and his poetry! — Stephen FitzGerald, Alphabet Box editor.

Background.

Where did you grow up?

I grew in Ikotun, a semi-urban town called “Ijegun” in the city of Lagos. Back then, my mother had a smallholding where we planted cassava, corn, waterleaf and sugarcane. I loved it, not for the tedious hoeing of hard ground — but for the adventure and promised extra meals.

Of course, I came back home every day with scratches from itchy plant leaves.

Did you have a favorite sport or hobby?

Football is my favorite sport to play and watch. Back in my childhood days, I joined the PrinceWorld Football Academy where I played the right fullback for the team, and won most valuable player in a few under-16 tournaments. We also went to camps and trials across Benin Republic and Ghana. Football could pass for my first love.

I played in band back then in my school and church. I drummed through night vigils and Sunday services when I was about 12.

Does your first name have a meaning or translation?

Yes. Nnadi translates to Father is alive. And my middle name is Chibuike, meaning God is my strength.

On Writing.

How many years have you been writing?

It all started from Facebook, sometime in 2018. I wrote a few memoirs, poems occasionally, and posted them. I officially started submitting to magazines in early 2020.

Who in your family encouraged you the most to be a poet?

I would say my sister. I can’t quote her words verbatim, but I remember she once commented on one of my random Facebook poem posts… “Save all these things you write, you’d get paid for it soon.”

What was your first job for pay?

I first worked as a school teacher, immediately after secondary school. The end result was a constant nagging headache and a truckload of paracetamol (acetaminophen) tablets.

Do you consider yourself as a writer first or poet?

I do consider myself first as a writer, open to explore the different possibilities and genres of art. I wouldn’t like to find myself caged in a box. Poetry has, however, been the most endearing.

You graduated from the University of Benin (UNIBEN) which was founded as the Institute of Technology, a research, medical and engineering school. By the time you attended as an English Literature major, had it become a welcoming place to also learn and explore fiction, poetry and creativity?

At the time, I would say No, it hadn’t. We never had a vibrant community or workshop for creatives — not until our third year, when the Creative Writers Workshop UNIBEN Chapter gradually made a collective effort to revamp the gathering.

The outdated syllabus and prescribed text didn’t help either — as whatever creative exploration was only achievable outside the academic system, by personal effort.

Although, I found a few Phonology & Morphosyntax courses helpful, while still working on my unpublished chapbook Subject Lessons.

Is there something about writing that remains a difficult challenge for you?

Yes. How to begin a poem is quite the problem for me, LOL. But there are no better ways to begin a poem than to begin, so I write it anyway.

How do you deal with writer’s block?

The mindset I would say is everything. I try as much as I can to read my way out of it. And, on a few occasions, I binge on movies or my favorite series.

Do you read as much as you write?

Oh! Yes, I do read as I write. It works in tandem these days — that when I’m not reading something, I am almost not writing or creating.

Are you a disciplined writer?

Discipline cannot be overemphasized in any art, and time is of great essence. I try as much to hold myself accountable, and in most cases fix monthly targets to meet. Sometimes, I fall short.

What’s an ideal setting to write poetry?

I do not think there is any ideal setting to write poems. Unlike a dinner date or orchestrated ballroom affair, poetry as I know it is spontaneous. Preparing for it might ruin the magic.

On the Stereotype.

In your Rough Cut Press interview with Amanda Lezra, you spoke of shutting out the stereotype of grief in your environment. Is this similar to or different from what some call victimhood or victim’s syndrome?

Yes, it is quite similar to the victim’s syndrome. And at best, “Poverty Porn” as Oris Aigbokhaevbolo — a well-known journalist — rightly calls it. A poverty of the imagination if, as young marginalized writers, we believe trauma via sentimentality is the sole path to getting published.

But in defense, it’s a reality we obviously cannot shy away from. I only do my best not to overflog it.

On Nature knows…

Please tell us about writing Nature knows a little about Slave Trade

The title was culled from a line of my poem titled Casualties. Nature knows… is a painstaking attempt to account for the racial subjugation, domestication of black marginalized voices from a contemporary point of view. On a more personal level, my experience on a building site with bricklayers helped a lot in fleshing out the narrative and achieving its authenticity and voice.

The last line where I wrote, “a decorum next to slavery, it demands your negro hands…” says a whole lot about the entire poem’s theme of endless strife, multitasking and belaboured hassle to make ends meet — which comes off to us here as an everyday banal.

In recent times, the urgency of the theme has given room for more poems, enough to curate a suite I would come to title “Nature knows…” and I am indeed grateful I wrote it when I did.

Who does “Pa” reference?

The persona “Pa” is a fictionalized father. I love as much to write in the first person, pronoun. That way, I have a more intimate relationship with the third persona, or what other voice there is, included in the poem. It makes it easier to share both their grief and joy.

On There is a gnawing…

What prompted you to write this poem? It puts me right there, in the sugarcane fields, by the way.

What prompted you to write this poem? It puts me right there, in the sugarcane fields, by the way.

A reminisce of my childhood farming experience, and the unchanging scenario of the Hausa or “aboki” as we fondly call them, out here on the streets with their wheelbarrows — all trying to sell enough to make ends meet.

But most importantly, the need to be more unified as people of different tribal boundings.

I’m impressed by the endings of both poems, their ambiguity and clarity.

As I earlier hinted, the last line of Nature knows… speaks of the silent struggles of an average black, marginalized individual. While the ending of There is a Gnawing… is as much a plea as it is a wake-up call for us to stick together as one — shunning terrorism, tribalism and all our individual differences.

Next.

Please tell us about your next project for publication. Subject Lessons is coming?

It’s an extraordinary study in the way language is explicit, and wounded with intrinsic experimental details of trauma, that sparks a new definition of family, race, history and identity. It is more of an experiment that keeps unfolding right before my eyes, with each passing day.

It’s currently unpublished. And, as soon as I find the right home for it, I will surely communicate in details.

I can’t wait.

Thank you so much for sharing my thoughts.

You’re quite welcome, Nnadi. Thank you for your time.

Become an Alphabet Box Patron.

Tips Help AB Publish and Pay Writers!

Log in to manage your payments